Cameras put bread on the table

Namibian youths are turning photography into a source of income, proving that creativity and determination can build sustainable livelihoods. This inspiring story follows young entrepreneurs

By David Bishop

Namibian social media users were up in arms last month when NamWater had the “temerity” to point out that the water levels in many of the country’s dams were dropping and a call on us to remain mindful of our water usage. Among the comments were that NamWater could not be “serious”, while many queried how we could be expected to be mindful of our water usage so soon after some of the dams had been “overflowing” or had their “sluices open”.

It always amazes me how short our memories seem to be here in Namibia. We have just survived what could have been a disastrous “Day Zero” scenario across most of the country after yet another drought. “Namibia is a desert country” has been repeated in headlines and talking points so often it has become a somewhat trite statement, and yet we still do not seem to get it!

NamWater was not saying in their dam bulletin that the dams were empty. In fact, they went as far as to say that the levels were higher than in previous years. But, as we all know, any future rains are at least a few months away, and even then they are not guaranteed, with most forecasts predicting a drier year in 2026 than 2025.

While there is undoubtedly a responsibility on the government to ensure the supply of potable water (and there is definitely room to criticise many aspects of this service), there is simultaneously an onus on all of us to play our part. As the former head of the Department of Water Affairs and Forestry, Piet Heyns, said at a presentation to the Namibia Scientific Society: “It’s the responsibility of all residents to become more efficient by having water-wise gardens and using water-saving devices, before it’s too late”.

“It’s the responsibility of all residents to become more efficient by having water-wise gardens and using water-saving devices – before it’s too late.”

One of the easiest ways of achieving massive water savings, as suggested by Heyns, is to step away from the Eurocentric fascination with lush green lawns. A symbol of status that researcher Alicja Wójcik says originated with “English and French aristocrats who nurtured lawns in front of their castles” and eventually, “entered the minds of common people as a symbol of money, power and prestige”. Lawns require about 20 to 25 litres of water per square metre every week – with those in hot, dry climates requiring even more.

Of course, as I have often said on the radio too, it is not just private lawns that are the problem, but municipalities across the country should also be looking at non-lawn public spaces. It is great that most public-space lawns, including sports fields and golf courses, are watered with non-potable water, but this is still water that could feasibly be used for other purposes. These lawns cover public spaces in most Namibian towns, and cities are also problematic in the politically exclusionary legacy they carry, besides being biodiversity dead zones.

We are fortunate in Namibia to have areas in most cities and towns where natural vegetation is allowed to flourish. However, making this the norm in both private and public spaces would significantly improve water conservation and biodiversity. Quoting various studies in an article for the University of Florida, Mark Hostetler and Martin Main point out that “the negatives of a landscape dominated by non-native plants far outweigh the positives for wildlife”, highlighting the fact that biodiversity measures, including bird numbers and diversity, bee populations and butterfly larvae, improve with the use of native plants.

So…

Until next time, turn off the tap, plant some native grasses and, most importantly, enjoy your journey.

Namibian youths are turning photography into a source of income, proving that creativity and determination can build sustainable livelihoods. This inspiring story follows young entrepreneurs

Rediscover the healer within. This wellness column explores how mindset, emotions, nature and spiritual awareness contribute to holistic healing and self-restoration, reminding us that lasting

Namibia urges urgent global action at COP30, highlighting climate adaptation, mitigation, and green hydrogen initiatives as the country strengthens resilience against climate impacts and promotes

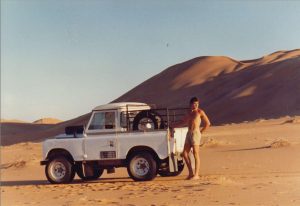

In loving memory of Dr Nad (Conrad) Brain – wildlife vet, conservationist, and bush pilot – whose work and stories continue to inspire Namibia’s conservation