Cameras put bread on the table

Namibian youths are turning photography into a source of income, proving that creativity and determination can build sustainable livelihoods. This inspiring story follows young entrepreneurs

By Muningandu Hoveka

Namibian artist and educator Fillipus Sheehama has gained recognition for his distinctive and refined use of mixed media. By recycling previously discarded materials, he creates visual statements that both reflect and critique contemporary life, focusing on themes of social and economic inequality. From his vantage point as an educator living and working in Katutura, Sheehama is constantly confronted with the fragility produced by radical economic inequality. This awareness is embedded in his work, with his material choices often mirroring the fragility of life in post-colonial Namibia.

Much of Sheehama’s work presents itself as large textiles constructed from unlikely materials. His materials of choice are discarded bottle caps, plastics, makalani nuts and calabashes. In recent years, his work has expanded to include organic discarded materials such as animal bones (from goats and cows), horns (from antelope, buffalo and cattle) and reclaimed metal. These flexible structures are held together with wire and rope, creating tension and harmony between the dissimilar elements. Drawing from the materiality of found and local objects, the artist ruminates on the communities and societies they come from.

Sheehama often travels to his family home in the northern part of Namibia, where he collects discarded shells of makalani nuts, as well as old calabashes and animal bones. Makalani nuts and calabashes are used in his work to preserve cultural knowledge and honour the contributions of women in northern Namibian households. These items are used to brew traditional beer, which in turn supports the livelihoods of many women in rural Namibia. In Katutura, where he lives, Sheehama collects buckets of bottle caps discarded at the local shebeens (bars). While these objects are associated with waste, they are also correlated with formal and informal economies. His powerful tapestries of these organic piths, in combination with discarded bottle caps, speak to the sheer amount of consumption and the abuse of alcohol, and juxtapose these with the opportunities for income generation that keep many people financially afloat.

By working consciously with his materials, Sheehama manipulates and dislocates familiar structures and surfaces, creating new ways of conceptually engaging with ordinary objects. “I actually find that it’s more flexible working with found objects, and it’s easy to connect them to the content that you would want to talk about, because the materials themselves have memories,” he says. Through his work, Sheehama poses questions to himself and the viewer: Where is culture in this? Where is the economy in this? Where is the inequality in this? In this way, an artwork can offer the viewer various ideas, and these can often be conflicting and contradictory.

Through his work as a lecturer, Fillipus Sheehama plays a critical role in shaping the next generation of Namibian artists at the College of the Arts in Windhoek. For Sheehama, teaching is an extension of his creative and philosophical approach to art, championing a research-driven approach to teaching. He views constant learning and discovery as essential to artistic growth, not just for his students, but also for himself. Drawing on his own experience of working with found materials, Sheehama encourages young artists to develop signature styles rooted in their environments and personal stories. “I came to learn about using found objects when I was a student. I have learnt that sometimes an artist has to be authentic, original and more innovative. It’s not only about the techniques, but also the materials.” He emphasises that innovation often comes from limitation, and that artists in Namibia must be empowered to see value in what is around them.

By reworking found and discarded objects, Sheehama transforms the overlooked objects that hold traces of labour, domestic life and social change into an everyday documentation of local traditions and social critique. His assemblages not only preserve fragments of the past but also reinterpret them, allowing forgotten or silenced narratives to resurface. In this way, his art operates at the intersection of memory and materiality, creating a visual archive that documents personal experience with collective heritage. Looking ahead, Sheehama continues to develop new work and plans to exhibit a new body of art in the near future.

Fillipus Sheehama holds a Bachelor of Arts Honours degree in Fine Art from the University of Namibia (2010). His work has been showcased in numerous group exhibitions both locally and internationally. Sheehama’s work can be found in collections of the National Art Gallery of Namibia and Museum Würth (Germany), to name a couple, and various private collections around the world.

Fillipus Sheehama’s work is currently featured in a group show at the Sweet Side of Thingz in Windhoek, located at Independence Avenue.

StArt Art Gallery

info@startartgallery.com

Namibian youths are turning photography into a source of income, proving that creativity and determination can build sustainable livelihoods. This inspiring story follows young entrepreneurs

Rediscover the healer within. This wellness column explores how mindset, emotions, nature and spiritual awareness contribute to holistic healing and self-restoration, reminding us that lasting

Namibia urges urgent global action at COP30, highlighting climate adaptation, mitigation, and green hydrogen initiatives as the country strengthens resilience against climate impacts and promotes

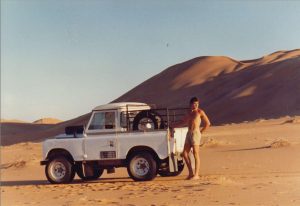

In loving memory of Dr Nad (Conrad) Brain – wildlife vet, conservationist, and bush pilot – whose work and stories continue to inspire Namibia’s conservation