Driving back from Matemba Village near Ruacana to Nakayale Private Academy for Orphans and Marginalised Children, I felt the little boy on my lap relax. He had stopped crying and sat in silence, his face set, revealing not a trace of emotion. I could only sense the vast cultural divide between us and the complexities of his thoughts and feelings.

The visit to his village was part of a project documenting the school and its children’s stories I was helping with. My mother started it. She established a school in Etunda, Omusati Region, where many children live beyond the margins, not to give them more choice – but to provide the only alternative to nothing. Nakayale is, in a way, my sibling.

The village was home to a few mud and grass huts, and as we arrived, children of all ages ran to greet us, excited to see their cousin and friend. Despite it being a weekday, they were not in school and posed happily for photos, seemingly unbothered by their dirty, tattered clothing. Our little Nakayale student looked out of place in his bright yellow shirt and green shorts. No adults were around, just a baby clinging to a little girl’s hip and some teenage girls giggling at the scene. I surveyed the surroundings — empty beer bottles, plastic debris, and a few goats and chickens that shared the huts at night due to the absence of secure enclosures.

The lack of water or bathroom facilities was evident. Suddenly, a commotion caught my attention. Our student had buried his face in his elbow, shaking with sobs. When I inquired about the cause, I learned nothing had happened, yet everything had.

It was painfully apparent that so much weighed on him. I picked him up and returned him to the vehicle, uncertain if he felt out of place or overwhelmed. Did he sense how thin the line was between his life and despair? Had we saved him or deprived him of his community? Meanwhile, other children laughed and posed for the camera, imitating influencer poses they must have seen on social media, a concept that baffled me in this impoverished setting. With data being costly in Namibia, access was limited for many, yet they were exposed to the pop ideals of Western culture.

We had brought supplies for the boy’s family, including mealie meal, sugar, and pasta. They mentioned that his grandmother was busy in the Mahangu field, and someone had gone to fetch her. We waited for her arrival, and when she finally came, her wrinkled face told of years of hardship. Upon seeing the supplies we brought, she clapped her hands in gratitude. After saying our goodbyes, we drove off, the forgotten children shrinking in the distance.

Illiteracy, poverty, and starvation are not unique to Namibia; they are global challenges. History, politics, and societal structures can cause people to fall through the cracks.

The initial idea was to financially sustain the school through profits from an agricultural project my mother also initiated. True to her ambitious nature, she sought to address challenges through sustainable business practices, promoting job creation over mere charity. Despite her immense efforts, the agricultural project failed to achieve sustainability due to various factors, including inconsistent water supply, droughts, pests, a struggling economy, and fluctuating fuel costs. But the school was a miracle.

An institution born out of a passion to transfigure education in rural Africa. In its early stages, Carmen de Villiers, an educationist with a long-held dream of alternative teaching methods, met Chrisna Greeff, who was committed to building a school. Together, they created Nakayale, a holistic, full- board learning environment that serves as a sanctuary for the brightest and most promising children from remote villages seeking to change their lives.

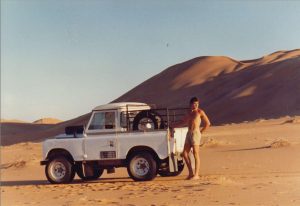

Carmen devised a system to assess the children’s perceptual awareness. Each year, she embarks on a journey in a bakkie, accompanied by a translator and assistants, gathering groups of children to evaluate. This thorough evaluation takes a month, requiring a deep understanding of each child’s circumstances and potential.

During her first expedition, Carmen discovered that these children displayed impressive physical, perceptual and other developmental abilities in most areas, surpassing those of children from more developed regions. Their balancing and climbing skills indicated resilience and adaptability not despite but because of a natural environment – without screens and with limited material resources.

The desperation to enrol children in the school was startling. Even for those with means, the nearest schools were far away, and every option was challenging. And Nakayale could only take fifteen children.

On the day the first intake of children moved into the hostel, the boys opened every tap in the residence. Water was streaming over the floor, flooding the hallways among shrieks and laughter.

They were like kids in a candy store. Except that it wasn’t candy. It was running water. It was a mattress to sleep on. On a bed. With luxuries like toothbrushes, toothpaste, and whole and clean clothes. Soap.

It was guaranteed three nutritious meals and two snacks every day without exception.